Over the last few weeks, I have been spending a lot of time with Carrie: The Musical (more on that next week!). In addition to being an amazing experience all around, the musical has given me the opportunity to think critically about how different performance mediums highlight or elide specific narrative elements or moments.

One of these that is particularly interesting is Carrie’s journey home through Chamberlain after the prom. After she has had her final destructive confrontation with her classmates, Carrie heads toward home and her momma, seeking comfort and safety. But the dark streets of Chamberlain lie between her and home, and her power leaves its mark every step of the way and with every individual she encounters along her path. Working within the spatial limitations of stage and set, Carrie’s long, lonely walk home is encapsulated in just a couple of lines of dialogue by Sue Snell, who says “I followed the path of destruction. It led from the school … through the town … and up Chamberlain Street … to Carrie’s house.”

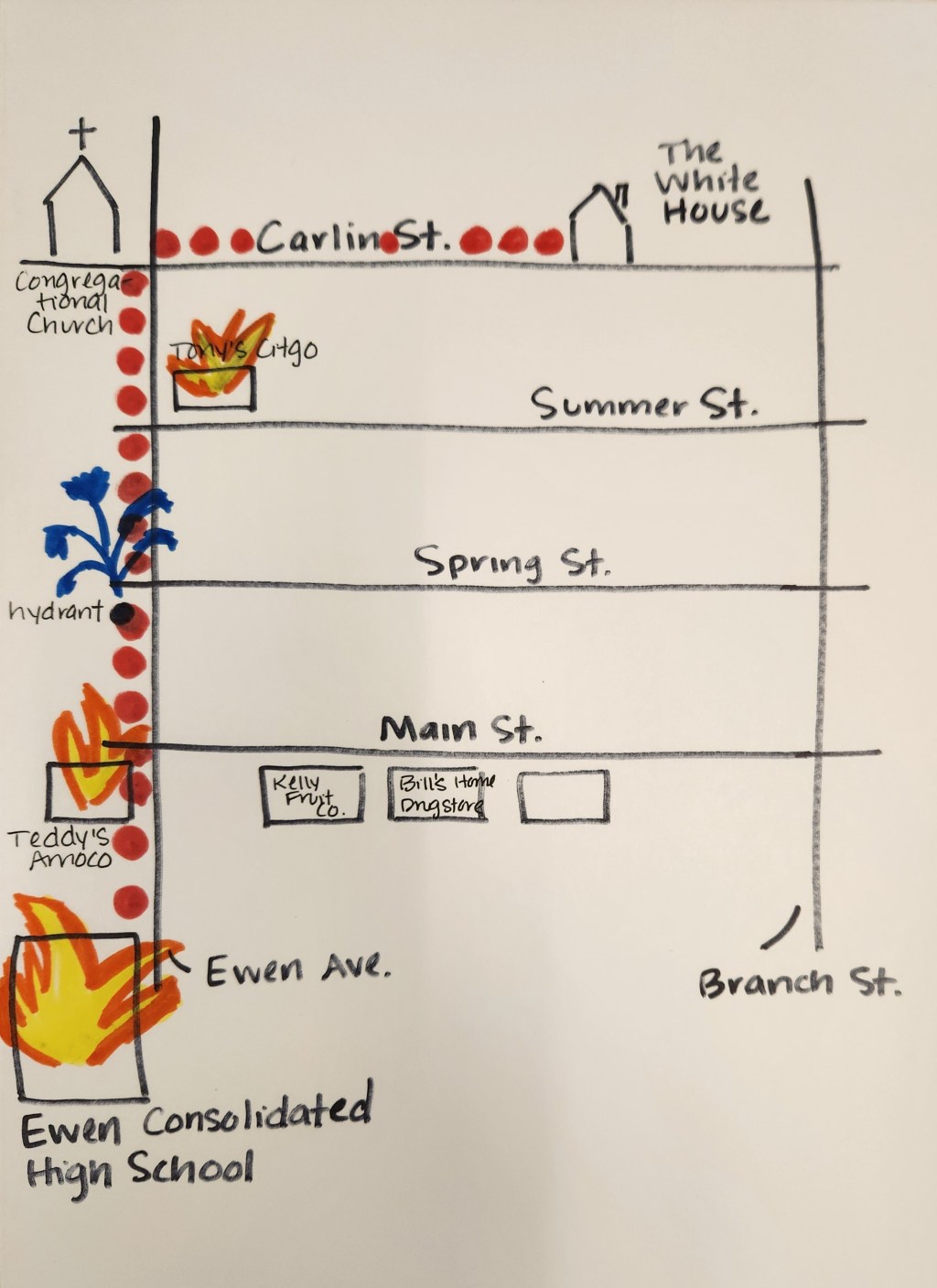

This description and summary version of Carrie’s journey inspired me to return to King’s 1974 novel with a literary geography lens to map Carrie’s walk. The walk home she makes at the beginning of the novel after the locker room incident and her walk home after prom mirror one another, both defined by trauma and blood: first, Carrie’s menstrual blood and later, the blood of her classmates and the other Chamberlain residents she meets on her way.

These differences reflect the directional focus of the suffering as well. In her walk home after the locker room scene, Carrie’s hurt is turned inwards, introspective and self-destructive. She is preoccupied with these fears and uncertainties as she almost absentmindedly makes her way home, with King describing how “She walked down Ewen Avenue and crossed over at Carlin at the stoplight on the corner” (25). She looks at the sparkle of the quartz in the sidewalk, the reflection on a neighbor’s picture window, and a child riding by on his bicycle. Her power is latent but awakening, as she uses her mind to make the boy fall off his bike when he shouts at her and the big window ripples in the sunshine, but this is an introverted, protective moment, as Carrie turns inward, separating herself from the hurt of the larger world as “She continued to walk down the street toward the small white house with the blue shutters. The familiar hate-love-dread feeling was churning inside her. Ivy had crawled up the west side of the bungalow … and the ivy was picturesque, she knew it was, but sometimes she hated it. Sometimes, like now, the ivy looked like a grotesque giant hand ridged with great veins which had sprung up out of the ground to grip the building” (29-30, emphasis original). She walks through the door and home is comfort and pain, love and danger, the place she always turns toward and the one she desperately longs to escape.

When Carrie makes her second walk home, the suffering is no longer Carrie’s—or at least not hers alone. On this second walk, her path of destruction is publicly remarked and clearly recorded, chronicled by news ticker reports, interviews with witnesses, testimony before the White Commission, and narratives constructed in the aftermath of Prom Night, along with Carrie and Sue’s perceptions and experiences. While each of these accounts is fragmentary, the combination of these multiple perspectives simultaneously trace Carrie’s progress through Chamberlain and set Carrie and Sue on an intersecting path. Leaving the high school, Carrie “began to reel across the lawn … a scarecrow figure with bulging eyes, toward Main Street. On her right was downtown—the department store, the Kelly Fruit, the beauty parlor and barbershop, gas stations, police station, fire station” (225). She opens fire hydrants as she goes, to make sure her fires can’t be extinguished, and she lights more along the way, using the gas stations she passes as incendiary catalysts. Carrie leaves her destructive mark on everything and everyone she passes and unlike her first journey, she is not turned inward, but is broken, severed from herself in some fundamental and irreparable way, as “She was unaware that she was scrubbing her bloodied hands against her dress like Lady Macbeth, or that she was weeping even as she laughed, or that one hidden part of her mind was keening over her final and utter ruin” (225-6). She leaves fire, downed powerlines, dead bodies, and sabotaged fire hydrants in her wake and while so much has changed, her heart and her footsteps take her back along the familiar route, toward home and her momma.

As I reflected on Carrie’s doubled journey from school to home, I immersed myself in the spatial descriptions of these two sections, paying close attention to directional details and descriptions. I imagined the two versions of Chamberlain through which Carrie passes, first as an outsider and later as a force of destruction and reflected on the ways that places hold both joy and pain, colored and shaped by what we endure, the safety we seek (however ineffective it may be, as in the case of Carrie’s house and momma), and the paths we follow.

[Page numbers for Carrie are from the 2011 Anchor Books mass-market paperback edition].